It has been more than a millennium, since the first seeds of tea bushes were brought to Japan by Buddhist monks. At that time, the culture of tea cultivation and tea drinking also came to Japan. The culture of tea became an important source of inspiration for various areas of art.

The art of Japanese ceramics, which originates from the Jomon period (around 11,000 BC to 300 BC), has been inspired by the culture of tea since then. Ceramic objects for tea preparation and drinking have become an important topic since this time. Ceramic art objects have been created especially since the flourishing of the Japanese Way of Tea [tea ceremony, chado].

Near places where tea was grown or where the culture of tea was cultivated, sites for ceramists were established soon after. The families of KATO Juunidai and Shutaro Hayashi come from such historical places.

![Teapot [shiboridashi kyusu], tea bowl [yunomi] and matcha bowl [chawan] by KATO Juunidai at an exhibition 2018](https://marimo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/KATO_Juunidai_kyusu_chawan_window_fine_M-1024x683.jpg)

Several places where senior samurai or nobles had their seat, came to be a cradle of the Japanese Way of Tea [tea ceremony, chado]. This includes not only the ancient main stand Kyoto, but also places such as the castle of Nagoya and the city of Sakai. Places such as Seto became important sites for ceramics manufactories.

Places such as Seto with special clay as cradle of historical ceramics

With a clay, which is so pure that it can be used in its unchanged state directly for ceramic works, the area around Seto can look back on now more than a 1,000-year history of ceramic culture. The place belongs to the six historic areas of ceramics manufactories [Rokkoyo, six old ceramic burning sites] in Japan. Already in the 13th century, the typical Seto ceramics were made there, namely Temmoku bowls glazed with ferric oxide [Tenmoku chawan, Temmoku matcha bowls]. This kind of ceramics, which were especially produced in the Kamakura period, are nowadays referred to as “old Seto ceramics [Ko-Seto].

![Temmoku matcha bowl with Ko-Seto-glaze [Ko-Seto Tenmoku chawan] by KATO Juunidai [KATO Hiroshige], the 12th generation of the KATO ceramic family](https://marimo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/KATO_Juunidai_Hiroshige_Temmoku_Chawan-1024x1024.jpg)

![Three matcha bowls [chawan] by KATO Juunidai [KATO Hiroshige], from left to right: Shino, Kuro-Seto, Aka-Raku](https://marimo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/KATO_Juunidai_Shino_chawan_M-1024x683.jpg)

The KATO family ceramic studio with a history from Tokugawa period until today

The succession of KATO Juunidai’s [KATO Hiroshige’s] actual ceramic studio is the only studio in Seto dating back to this time. In 1656, the ceramic master Hikokuro withdrew from the other ceramic families who were protected by the Tokugawa Shogun. In that year, he founded the creation site of today’s KATO family. Now we admire the works of KATO Juunidai [KATO Hiroshige], who belongs to the twelfth generation of the family.

The three-stage creative process of ceramic works

KATO Juunidai [KATO Hiroshige] describes the process of creating ceramic works in three steps: the first is the selection of materials. To this purpose, belong the selection of the clay as well as the selection of materials for glazes. The second step is the shaping and the last step is the firing. For each of the three steps, KATO Juunidai sees very different aspects in the foreground.

During the first step, namely the selection of the clay and the materials for the glazes, the natural environment of the ceramist is in the foreground. This is how KATO Juunidai took the idea from his grandfather KATO Juudai [KATO Senzaemon]. As it was shared from generation to generation in the tradition of the KATO ceramist family since the Tokugawa period, KATO Juunidai always emphasizes on the fact that all materials stem from nature. To the generation of his grandfather, it was still obvious that this is so.

However, nowadays it has become common in many ceramics manufactories to quite easily order and receive finished glazes and clays from a manufacturer. However, KATO has made a conscious decision for that, not to choose this way, but to follow the tradition of his family. For him, this means that he gets the different varieties of clay and glaze components from the soils of different mountains and hills in his natural environment.

As already mentioned in relation with the history of the ceramist site Seto, the soils that are found are so pure that they can be directly used for the production of the ceramic works. KATO uses the different soils of his region for many of his works without mixing them. However, for some of his styles of works, he uses also mixtures of certain clays.

So, like the clays, all raw materials for the glazes of KATO Juunidai stem from his direct environment. Iron-containing soils, which are used for the traditional “Ko-Seto glaze”, play an important role here among others. Depending on the other components in the glaze, and depending on the firing process, however, the facets of the resulting glaze colours vary significantly. For example, this results for example in matt-grey-brown glazes to high-gloss black glazes. In addition, red glaze is also produced using iron-containing soils. This includes the glaze of the style “Tetsu-Aka”, whose direct translation is “iron red”.

In contrast to the first step, which is characterized by the natural environment, the second step depends on the artist himself. An important decision regarding the shaping consists initially in the approach if the work is rotated on a potter’s wheel or if it is moulded by hand. Obviously, the two procedures of design can be combined together. For example, a matcha bowl [chawan] can firstly be rotated on the potter’s wheel, and then deformed with the hands. In addition, other procedures can be added. Among others, this includes reductive work with various tools such as knives or spatula, which are used for targeted and accurate removal of the clay directly on the object.

Regardless of fact, which types of shaping the ceramist chooses or combines with each other, the shaping depends mainly on the essential artisanal skills of the artist. Nature only plays a role in it to a certain extent. For example, one of the factors influenced by nature is how complicated or simple the particular clay extracted from nature can be processed. Like it is with the shaping, it can also be said concerning the glazing, that the focus here is on the skill and experience of the artist.

![Different designs of matcha bowls [chawan] in comparison: Ofuke by KATO Juudai, Doukei Chawan by KATO Juudai, Tetsu-Aka by KATO Juunidai.](https://marimo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/KATO_Juudai_Chawan_No5_g_V2-1024x1024.jpg)

However, during firing there are a number of factors, which, depending on the type of oven, depending on the type of firing process and the use of other means, can never be fully controlled. A good example of this is, among others, the exact position of the respective work in the oven. Depending on the distance and orientation to the heat source, the natural glazes develop very differently. Black clays may be accompanied by reddish nuances. Matte grey-black tones can turn into high-gloss deep black tones. In addition, the glazes can run more or less strong, and more or less significant (desired) fissures can appear. Here, the interaction of the glaze with the clay during the firing process plays a crucial role.

![Matcha bowl [chawan] in Ofuke style, high form [kousou] made by KATO Juunidai in 2019 – set of 25 pieces](https://marimo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/KATO_Juunidai_Ofuke_Chawan_V4.jpg)

The connection with environment and tradition as a core element in the creative process

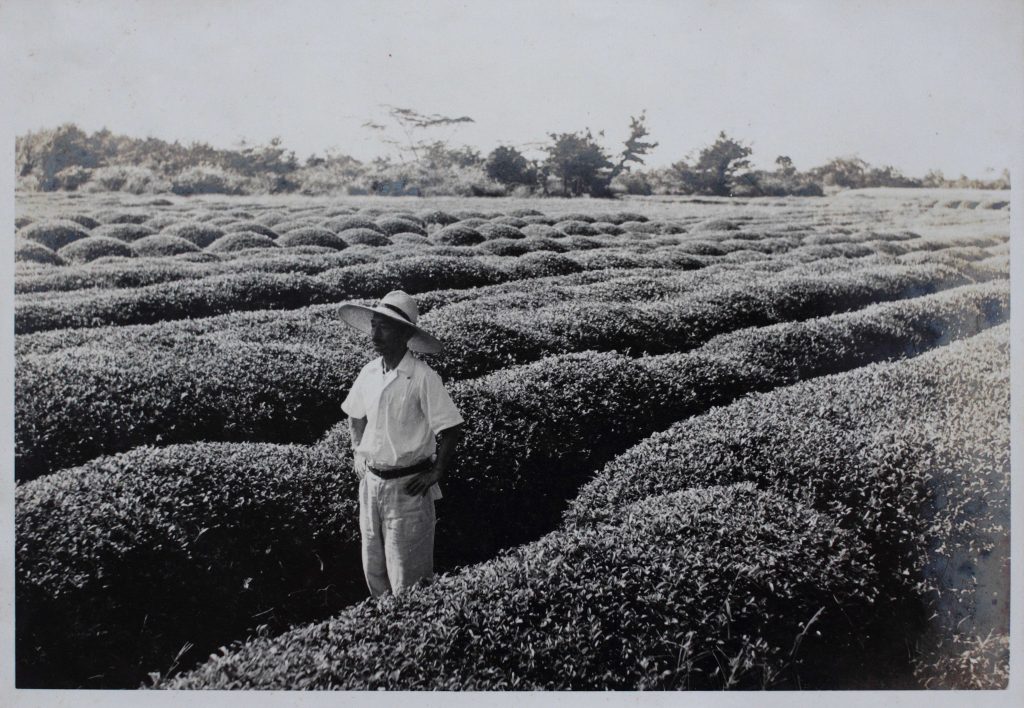

Similar to the ceramist family KATO, the relationship with the natural environment as well as the cultivation of certain family traditions, plays an important role for Shutaro Hayashi. When Shutaro’s great-great-grandfather Kisuke Hayashi founded the tea garden in 1897, he used seeds from tea bushes that he brought from the far Shizuoka prefecture, to Kirishima. As mentioned above, in Kirishima, since 1219/1220, there has been tea cultivation with bushes from seeds, which stem from the Uji region near Kyoto. Consequently, Shutaro’s great-great-grandfather Kisuke Hayashi founded the first tea garden in Kirishima, whose bushes were grown from seeds from Shizuoka Prefecture.

The beginning of the history of the Kirishima tea garden of family Hayashi thus represents in this sense a certain break with the tea growing tradition in Kirishima that exists until then. One result of this is that the tea bushes of the Hayashi family in Kirishima are not genetically related to the seed-grown tea bushes of other gardens in Kirishima. The seed-grown tea bushes [zairai-shu] from the tea garden founded by Kisuke Hayashi in 1897 are therefore unique in Kirishima.

Zairai as a symbol of preservation of tradition and new bushes as an expression of one’s own style

Also, in the following two generations, Shutaro’s great-grandfather and Shutaro’s grandfather created more seed-grown tea garden parcels. For the sorts of tea from seed-grown tea bushes, Shutaro still nowadays harvests the leaves from these old bushes. Today, the youngest of these bushes [zairai-shu] are a little more than 60 years old, while the oldest are already over 100 years old. Shutaro uses the leaves of these bushes for a certain range of his tea sorts, such as the Miumori Kirishima Sencha, Asanagi Sencha, or the Miyama Kirishima Sencha.

The production of tea from these old bushes has thus been passed on from the first generation of Hayashi family until today. Shutaro represents already the fifth generation making tea from these old bushes. Meanwhile, Shutaro has also planted other types of tea bush varietals, which he uses in a more modern way. With the old tea bushes, Shutaro mostly cultivates the processing style of his father, which his father learned from the grandfather. In the first and second generation, the tea bushes were still processed in the form of a dry heating [kamairi-cha].

The transition between generations in the interplay of the production style: Kamairicha and Sencha

In the third generation of family Hayashi, the introduction of a different production style took place, namely the steaming [sencha]. At that time however, the steaming was very short and therefore less intensive [asa-mushi sencha]. Thus, despite the change in production style, the finally produced leaf was quite similar in many criteria to the dry-heated tea [kamairi-cha]. When processing the leaves of the old bushes, Shutaro Hayashi still maintains the production style of light steaming [asa-mushi]. At the same time however, Shutaro also pursues another preference with the new tea bushes he planted with his father: He steams the leaves of tea bush varietals like Asatsuyu more intensively [chu-mushi] to [fuka-mushi]. Shutaro thus maintains the tradition of his family, but at the same time develops new styles.

In addition, regarding the Hayashi family’s relation to nature, there are traditions that are transmitted from generation to generation. But also, in the relation to nature, there are changes that have to do with the current of time. When Shutaro’s great-great-grandfather Kisuke Hayashi founded the tea garden, it was not common to use pesticides and chemical fertilizers produced by the chemical industry in tea cultivation. In this respect, it could be said that at that time at the end of the 19th century, it was a tea garden that cultivated tea in a natural way.

Also, in the second generation of the family Hayashi, the tea garden in Kirishima was managed in this way. However, there was a bigger turn in the third generation since it became common in Japan to use pesticides and chemical fertilizers in tea cultivation. However, the fourth generation, namely Shutaro’s father Osamu shortly afterwards decided to return to the original tradition of tea cultivation. Shutaro learned this form of organic cultivation from his father Osamu, and he still maintains it until today.

Therefore, in the fifth generation, Shutaro adopts from his father the return to tradition, but optimizes the methodology of organic cultivation as part of his aim. Concretely, this means that Shutaro has set itself the goal of producing natural teas, which moreover inspire the tea lovers with a particularly intense umami. To create a special umami in a natural way, an umami in harmony with nature is an ambitious goal.

In the same way that KATO uses natural resources in his environment to select materials for his clay and glazes, Shutaro uses only materials that stem from nature for the cultivation of his tea bushes.

Tea and ceramics from the perspective of the artistic creation process

Tea is often considered in its function as a drink. The result of this consideration is that other facets of the topic of tea thus remain in some way unseen. Similarly, ceramics such as tea bowls or tea pots are often seen in their function as a utensil. Certain aspects, perhaps even secrets, remain that way, hidden from the view of the observer.

In addition, the evaluation of what is considered as “good ceramic“ or “felicitous tea” depends on which function, or aspect the observer considers as important. The question of whether tea and ceramics are particularly considered as a drink or a utensil or on the contrary as an artistic expression, leads to very different results in the evaluation.

A point of view which among others is inspired by the Japanese Way of Tea [chado, tea ceremony] is not to separate the two points of view. Therefore, it follows that tea as well as ceramics are both everyday objects or simple drink and an artistic way of expression. At least both – tea and ceramics – play a central role in the framework of the artistic performance “Way of Tea” [chado, tea ceremony]. During the ceremony, not only the state of the final works “tea” and “ceramics” is considered, but also their origin and their history.

While certain nuances of a glaze on a tea bowl for the tea ceremony [matcha chawan] as KATO produces can only be achieved with great skill, perhaps even only with luck, the question of which nuances the artist wants to produce is also important. Therefore, the creative process is about the interaction of things that can be planned (stylistic purpose) with things that are only conditionally influenceable. Therefore, the creative process is about the interaction of the stylistic project, that is, what can be planned with what is only conditionally influenced. While the artist can determine the shape of the bowl, certain processes in the oven can only be influenced to a limited extent.

The process of the creation of a matcha bowl [chawan] thus incorporates the artist’s stylistic preferences, which again represent an interaction with the tradition of the artist’s environment. Besides, that genesis also includes facets of what appears more or less randomly. In addition, the application of the glaze can take place as planned, for example in the form of defined motifs or graphic elements, as known from the style Oribe. On the other hand, the application of the glaze can take place for example, by sprinkling the glaze with the help of a brush. The element of artistic and craft experience then interacts with the element of coincidence.

![Oribe style matcha bowl [chawan] by KATO Juunidai [KATO Hiroshige] – unique piece K12-03](https://marimo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/KATO_Juunidai_Chawan_Unique_K12-03-1024x1024.jpg)

As KATO expresses it, for him the firing of a ceramic work goes along with hands folding and praying for the formation of a successful art object during the firing process. Meanwhile, KATO has the possibility to regulate the temperature over time, but he cannot look inside the oven. Similarly, while steaming his tea leaves, Shutaro Hayashi meets the challenge of trusting his awareness and intuition. While regulating the temperature and the intensity of the steaming, he cannot still surely foresee how his work (the tea) will end up with a distinctive flavor. The same applies to the decision on which day exactly the shading of the tea bushes [kabuse] starts, as the harvest time is also the actual endpoint of the shading. Since the harvest day cannot be certainly foreseen at the beginning of the shading, the decision about the start point of the shading relies to a fundamental degree on the experience and on the intuition of the artist.

The intuition, experience and relationship to the environment thus shape the process of creating the works of both artists – Shutaro Hayashi and KATO Juunidai – in a fundamental way.